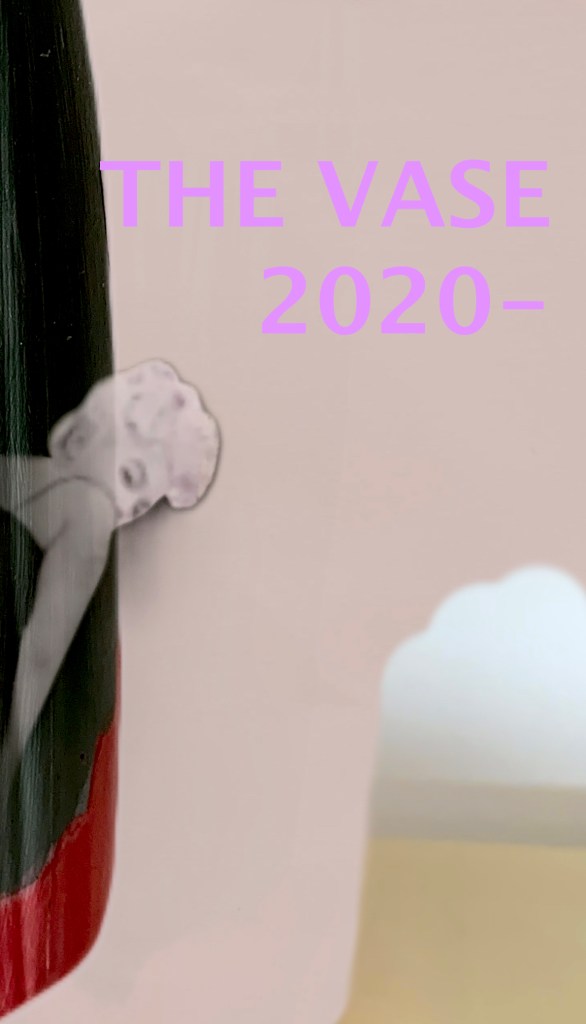

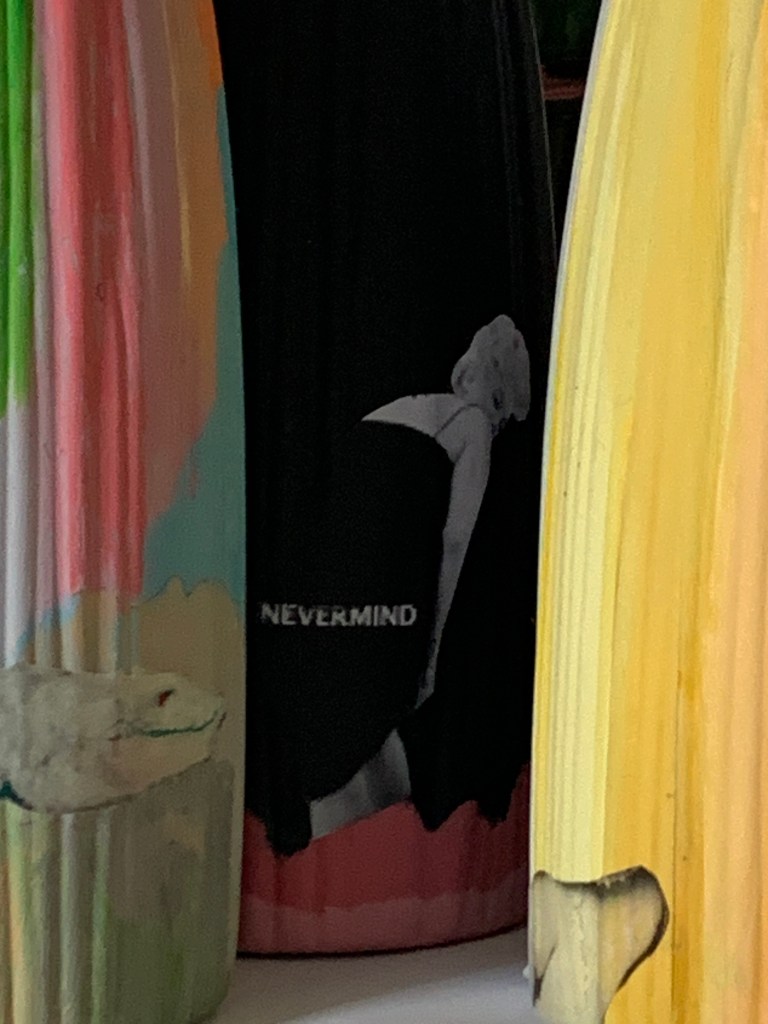

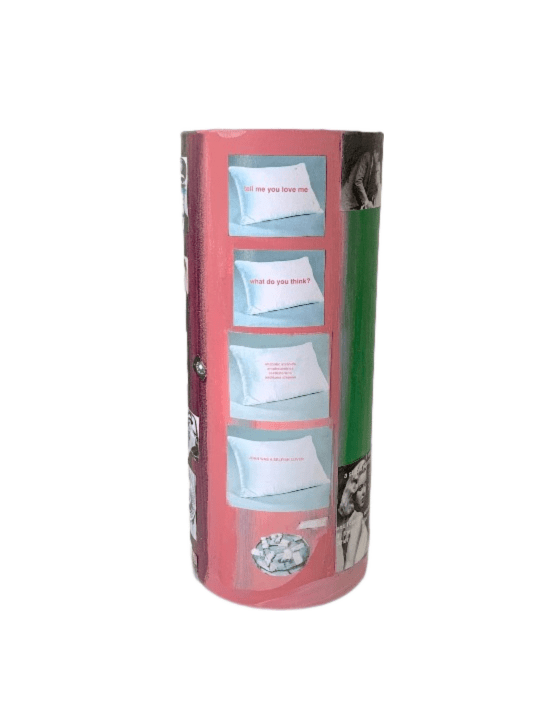

I began painting vases during lockdown. Importing anticeramic vases from china

and using emulsion and acrylic paint and my photocopy machine to create collage.

Reflecting on my cultural exposure with autobiographical references .

In short, the pot, as signifier, is nothing other than a symbol of culture as a whole and holds the integral but subtle power to resound every aspect of that said culture.

The Lacanian ‘Pot’

In his tenth seminar, Lacan contends that “civilization is already complete and in place when (…) [the] first ceramics [appear]” (Lacan, 2014 [2004], p.168). The ceramic vase contains everything, and not in the least “man’s relation to the object and to desire (Lacan, 2014 [2004], ibid.). The fundamental dimension of the vase is that it encapsulates a void and that the barring of this void begins human action – the filling or emptying of the pot or vase. It is not that difficult to corroborate

Lacan’s assertions. A short exploration of the Jōmon period (10,500 – 300 BC) already highlight the importance and the centrality of the notions of container and contained for the blossoming of culture. While in the early Jōmon period pots were almost exclusively used as storage units, allowing a more sedentary life near nut-yielding forests to develop, pots were, before the Jōmon period came to a close, adapted for burial, ritual, economic, cooking and aesthetic purposes (Brown, 2008). Pots became more varied; “Upright pots for cooking and storage, large bowls for cooking, narrow-necked vessels for steaming foods, and cups for drinking”, and large inverted pots, pots often with no bases or with holes drilled in their bottoms, were used to ‘store’ the remains of the dead, chiefly those of children” (Brown, 2008, p. 68). In short, the pot, as signifier, is nothing other than a symbol of culture as a whole and holds the integral but subtle power to resound every aspect of that said culture.

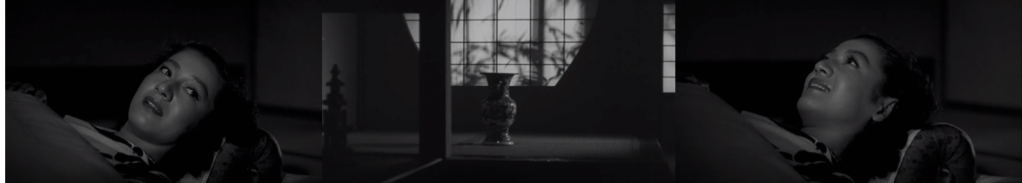

OZU LATE SPRING Acrylic and paper on glass 21 x 10 cm 2023

THE VASE AND THE PILLOW SHOT

Ozu’s vase within the cinematographical metonymy: an interpretation

And then suddenly the first vase-pillow-shot enters the concatenation of images.

It confronts the spectator a stillness, a stillness that evokes nothing other than the nature of Japanese traditional culture as such – and the lives it influences (Note 1).

The shot of Noriko’s changed facial expression after the first vase-pillow-shot but before the second of fundamental importance as it changes the mood of the evocations. Life – her life – and the stillness of Japanese traditional society that effected her trajectory are given, due to her expression, a more tragic dimension.

That is the main reason why the second vase-pillow-shot is even more moving than the first. In the light of evoking the whole of traditional culture, her sacrifice, i.e. her consent to an arranged marriage, is revealed as nothing but an inescapable subjective tragedy. In more general terms, the stillness of traditional culture is unearthed – as the evocative vase-pillow-shots pass by – as the main cause of tragedies for modernized Japanese female subjects.

Notes:

Note 1: The decision of her father to remarry is also evoked as fixed and unchangeable. One could thus even say the vase represent the acceptance of that was cannot be changed, i.e. her own marriage and her father’s remarriage in particular and the traditional ways in general.

The Pillow shot is a technique that stands right at the border between narrative and non-narrative cinema

The idea of the “pillow” word or phrase is something that was first used to describe phrases in classical Japanese poetry – these are often short phrases that appear as the first line of a poem, but don’t add anything to the literal meaning of the poem. Instead, their purpose is more for rhythm, or atmosphere, or perhaps to introduce a subject, or modify a noun. The idea of a pillow is much better known when applied to cinema – most notably the work of Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu. “pillow shot” is a cutaway, for no obvious narrative reason, to a visual element, often a landscape or an empty room, that is held for a significant time (five or six seconds). It can be at the start of a scene or during a scene. At a minimum, in Ozu’s work, these pillow shots inject a sense of calm and serenity and contribute to the elegant and stately pacing of his movies

The term “pillow shot” was coined in connection with Ozu’s work by the critic Noël Burch in his book To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema: “I call these images pillow-shots, proposing a loose analogy with the ‘pillow-word’ of classical poetry.” In a note, Burch cites Robert H. Brower and Earl Miner thus: “Makurakotoba or pillow-word: a conventional epithet or attribute for a word; it usually occupies a short, five-syllable line and modifies a word, usually the first, in the next line. Some pillow-words are unclear in meaning; those whose meanings are known function rhetorically to raise the tone and to some degree also function as images.”

So (by analogy) a pillow shot serves as a visual “nonsense-syllable” or non sequitur that creates a different expectation for the next scene.

In essence, it’s a still-life image that is cut into the body of a film in a way that doesn’t advance, but instead stalls the narrative.

see how the vase in Late Spring shows the containment of emotion, or the train tracks in Tokyo Story an oncoming darkness.

the pillow shots, he argues, are examples of mu, the concept of emptiness in Zen art. The pillow shots are Ozu’s version of mu, and they break off sections of conversation – unlike the critics who see the pillow shots as supplements to the narrative, Schrader takes a slightly different approach. He instead claims that the narrative is there to give meaning to the pillow shots; “the dialogue gives meaning to the silence, the action to the still life.”

Abé Mark Nornes, in an essay entitled “The Riddle of the Vase: Ozu Yasujirō‘s Late Spring (1949),” observes: “Nothing in all of Ozu’s films has sparked such conflicting explanations; everyone seems compelled to weigh in on this scene, invoking it as a key example in their arguments.” Nornes speculates that the reason for this is the scene’s “emotional power and its unusual construction. The vase is clearly essential to the scene. The director not only shows it twice, but he lets both shots run for what would be an inordinate amount of time by the measure of most filmmakers.” To one commentator, the vase represents “stasis,” and is thus “an expression of something unified, permanent, transcendent.” Another critic describes the vase and other Ozu “still lifes” as “containers for our emotions.” Yet another specifically disputes this interpretation, identifying the vase as “a non-narrative element wedged into the action.” A fourth scholar sees it as an instance of the filmmaker’s deliberate use of “false POV” (point-of-view), since Noriko is never shown actually looking at the vase the audience sees. A fifth asserts that the vase is “a classic feminine symbol.” And yet another suggests several alternative interpretations, including the vase as “a symbol of traditional Japanese culture,” and as an indicator of Noriko’s “sense that . . . [her] relationship with her father has been changed.”

The reference to such shots representing a “permanent, transcendent” element is interesting. The directorial gaze is a nonhuman one, somehow, isn’t it? As anything truly objective is? By holding such shots, Ozu emphasizes the irrelevance of human activity to nature.

Emulsion and acrylic paint and paper on glass 20 x 8 cm 2023